MAG’s 2019 Annual Report returns to the format of an integrated report, breathing new life into its tradition of providing a more complete view of the essence of the group as a whole, unrestricted by the narrow confines of more traditional positivist conservatism.

This means that mandatory financial data are accompanied by information of a more strategic, organisational and business nature. The aim is to provide a better overview of the MAG Group, highlight the sustainability profile of its development model and offer a more comprehensive view of the financial and social implications.

The decision to return to an integrated report as adopted some years previously takes the group step by step towards increasingly sophisticated reporting which offers an in-context view of financial performance, setting out the links with other aspects the group is involved in.

These relate to the perspectives and issues raised by the various stakeholders directly and indirectly involved in MAG’s business project.

Raising the very notion of the stakeholder implies an ontological view of business underpinned by principles such as corporate legitimacy1, or the stakeholder fiduciary principle which binds a company and its stakeholders.

Taking a purely pragmatic approach, stakeholders can be defined using one of the older definitions2 which identifies stakeholders as those groups without which a company would cease to exist.

The development of reporting formats and methods goes back to company culture, in an attempt to respond to a post-modern view of social responsibility by pursuing a balance between the polar opposites of Goodpaster’s stakeholder paradox3: ethics and business. Its pragmatic solution is to appeal to each stakeholder to act responsibly.

In addition to ancient origins4, the issue of general responsibility for economic conduct can also be observed in more recent historical periods – such as in many European countries hit by the industrial revolution which upended the existing social networks in the nineteenth century – when businesses introduced health care and savings schemes and support for widows, orphans and the elderly to compensate the loss of social support.

Models like Olivetti’s have ably demonstrated the role of corporate responsibility in shortage economy, embodying the concept of a company that increases the wellbeing and the personality of workers and facilitates the achievement of the aims of human life5.

Over and above the reforms introduced into many legal systems, socio-economic changes of recent years resulting from the various crises have changed social stakeholders’ expectations of companies.

Accordingly, the voluntary adoption of an integrated reporting system is not only a conceptual aspiration but focuses on concrete objectives of overcoming the long-standing asymmetry of disclosure between the various stakeholders, making strategic use of the disclosure of company objectives, business behaviour and corporate identity.

In anticipation of this, MAG has over time also voluntarily implemented a best practice-inspired governance system commensurate with the group’s size and maturity.

This includes the implementation of an internal control and risk management system pursuant to Legislative decree no. 262/2005, with the aim of moving towards an integrated compliance regime which is not merely “legislative compliance” but which ensures correct, transparent internal reporting and reporting to stakeholders in general.

This report also includes a first set of environmental indicators identified in accordance with the recommendations issued by the IIRC6, which have been collected for a five-year period, showing the limited environmental impact of the group’s industrial activities in figures and highlighting the group’s awareness of environmental issues.

In a more nuanced interpretation, the business/environment relationship embraces the technological and innovative factor which represents a key competitive edge for MAG but which also harbours potential linked to R&D’s contribution to the development of air travel which is poised to undergo seismic shifts.

Integration is also a term that describes MAG’s products and services, made up of systems and equipment which share certain strategic technologies.

Envisaging and interpreting technological developments is vital, given the speed that innovation is changing the way we live and contributing to changes in human culture.

Norbert Wiener7 defined his cybernetic science from the Greek kubernétes8, i.e., the art of steering, as the practice of those who seek in the machine the creative impulse of the creator who wants to become God. As the concept of the supremacy of the brain over the hand gained groun9, every important turning point in the history of technology has taken on an anthropological sense of progressive liberation of the human species from natural and social problems.

Companies are powerful agents of innovation, driving change by consolidating their competitive edge on the market.

This role has seen MAG forge a network of relationships, mostly with universities and research bodies, facilitating the exchange of knowledge, access to testing facilities and the dissemination of findings beyond the specific area of product of process innovation.

Presenting non-financial information is a form of storytelling about an entire community of people throughout MAG’s various internal and external spheres of interest. Where possible, MAG has sought to avoid using formal terms and expressions that have lost their substance.

With respect to methodology, certain clearly identified sections in the first part of this report include information that the group has provided on a voluntary basis with reference to the GRI G4 Guidelines and the regulatory standards defined at EU level10 and transposed into Italian law by Legislative decree no. 254/2016.

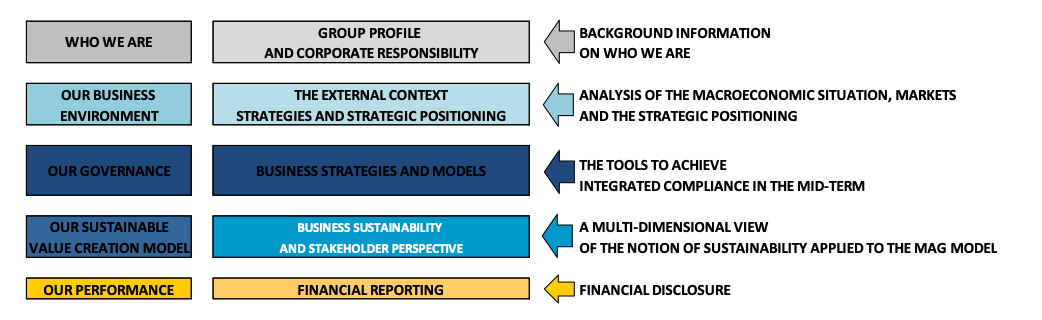

A general overview of how this information is structured shown below:

The 2019 Annual Report includes the DIRECTORS’ REPORT, the CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS AT AND FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 SEPTEMBER 2019 and the SEPARATE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS AT AND FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 SEPTEMBER 2019.

Andrew L. Friedman, Samantha Miles, Stakeholders. Theory and Practice, Oxford University Press, 2006, introduction, pp. 1-2. ↩

Stanford Research Institute, 1963. Ref. Igor Ansoff, Corporate Strategy, McGraw-Hill, 1965, p. 34, comment by Johanna Kujala. ↩

Kenneth Goodpaster, “The Stakeholder Paradox”, Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, December 2007, vol. 20, Issue 6, pp. 515-532, Karsten Klint Jensen. ↩

Giuseppe Furlani, Leggi dell’Asia Anteriore Antica, Rome, Istituto per l’Oriente, 1929. More than 4,000 years ago, the Hammurabi Code required carpenters, tavern keepers and farmers to abstain from negligent conduct that could irreparably damage others, punishable by the death sentence. ↩

Pietro Onida, L’azienda. Fondamentali problemi della sua efficienza, Giuffré, Milan, 1955, pp. 1-2. ↩

International Integrated Reporting Council ↩

God & Golem Inc., A Comment on Certain Points where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion, Boston, The MIT Press, 1964. ↩

Palinurus, Aeneas’s helmsman (“Nunc me fluctus versantque in litore venti”, Virgil, Aeneid, VI, 362). ↩

André Leroi Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, Mimesis, 2018. ↩

Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial information. ↩

![MAG Annual Report 2019 [EN]](https://finance.mecaer.com/2019en/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/06/Logo_up_big_2.png)