The crisis swiftly wiped out the progress made since the 1990s in reducing poverty. Households dependent on unstable wages or day-to-day jobs that do not have an income or health safety net have been heavily penalised by the restrictions. Migrant workers that are far from their country of origin have had to manage without traditional support networks. Some estimates1 indicate that around 90 million people have fallen into extreme poverty (less than USD1.9 per day).

The effects of the crisis have hit the most financially vulnerable the hardest: young people without job security, women and small business employees, particularly in the worst affected sectors.

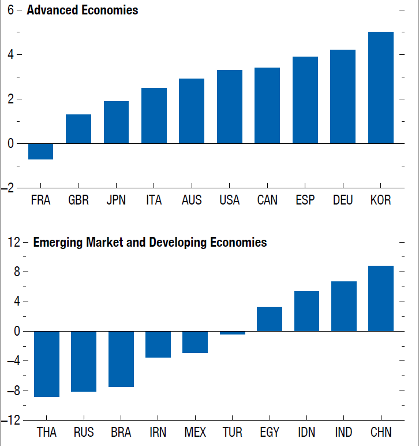

Inequality, as measured by the Gini index2, is now greater than in the early 1990s in many advanced economies and emerging countries.

Possibilities such as working from home favoured categories with higher education levels, better access to technologies and the availability of digital tools and connectivity networks.

Like distance learning for schoolchildren, the possibility of working from home represents a big step forward. According to the School of Management’s Smart Working Observatory of the Milan Polytechnic University, 6.58 million workers worked from home in 2020, involving 97% of large businesses, 94% of the public administrations and 58% of SMEs.

The combination of this rapid revolution of the world of work and the challenge of managing children and their education during the prolonged school closures which took place in almost all countries around the globe deserves particular attention.

According to UNESCO, around 1.6 million school and university students of all ages were affected by this phenomenon.

For children, the interruption to their schooling meant missing out on the opportunity to learn, and was more pronounced in families where poverty and disadvantage go hand in hand with the unavailability of the right tools and parental inability to bridge the educational gap.

In some cases, school closures also meant depriving children of nourishment and access to a healthy environment, as in many countries or in disadvantaged areas in advanced economies, schools provide free meals for low-income families.

Not going to school also exposes these children to greater risks of violence and exploitation, particularly in poorer countries3.

The closures will probably have long-term economic and social effects unless the opportunities offered by the overhaul of economic policies are seized, so as to restore an adequate accumulation of human capital.

In the absence of adequate measures, inadequate school achievement or irregular attendance lead to lower lifetime income which, although not comprehensive, is an accessible gauge of prosperity.

![MAG Annual Report 2020 [EN]](https://finance.mecaer.com/2020en/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2021/02/MAG2020.png)