The economic situation has all the characteristics of an unforeseen short-term shock, with trends moving in direct correspondence with the path taken by the spread of the epidemic, causing a contraction in the gross domestic product of the major economies.

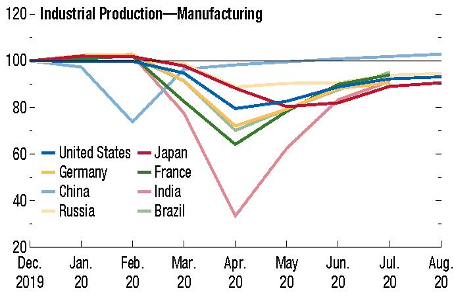

Following the great lockdownof early spring, the partial reopening of the western economies enabled a recovery in the third quarter of 2020, with encouraging figures particularly in industrial production1, albeit insufficient to indicate the extent of the possible recovery.

Indeed, a further indication of the opportunities that arise when contagion is kept under control came from the surprising results posted by some Asian countries during this period, mainly China and South Korea.

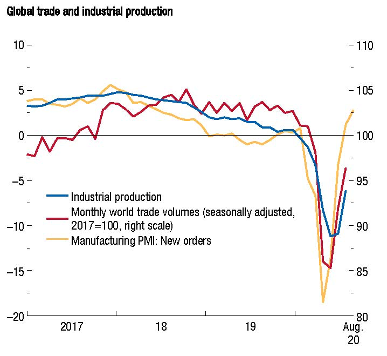

World trade also showed encouraging signs of recovery in the third quarter, with the dual factors of an easing of restrictions in the west and the strong Chinese contribution having a significant impact.

Global trade2 indicators reflect the uniqueness of the current macroeconomic situation. Unlike previous crises, the services sectors have gone into a deep recession while the main manufacturing sectors have been impacted to a lesser extent.

Indeed, this structural aspect has also meant a faster and larger rebound in domestic product when restrictions were temporarily eased, offering some reassurance as to the post-Covid opportunities.

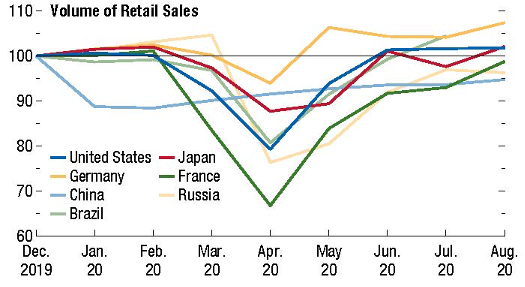

Retail sales volumes closely followed the trend of the relevant market, with the Chinese market leading the way.

The effect on aggregate demand3 was the redistribution between different types of goods, with demand for foodstuff and medical supplies offsetting the weakness of other sectors or the impact of interruptions of some supplies.

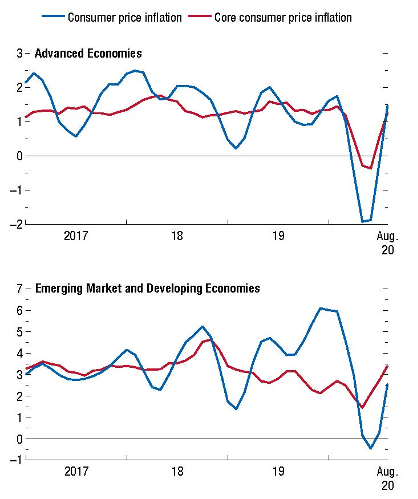

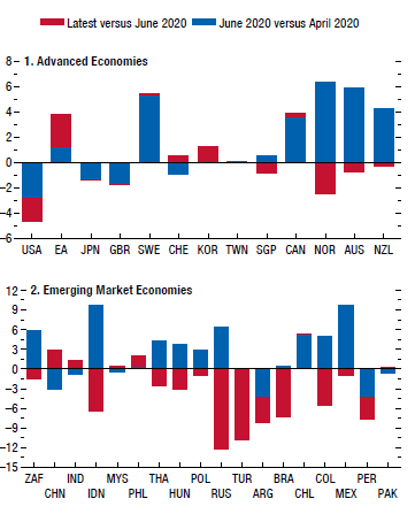

In the advanced economies, the combined trends resulted in more steady inflation compared withpre-crisis levels.

In the main emerging markets, inflation4 decreased more gradually, with marked rebounds in cases such as India, where interruptions to the supply chain and rising foodstuffs prices generated a spike in inflation.

Although approaches differed, for instance between the United States and Europe, governments responded vigorously to the swift spread of the epidemic. In most cases, the response comprised a suite of measures, including restrictions on individual and collective freedoms unprecedented in modern times.

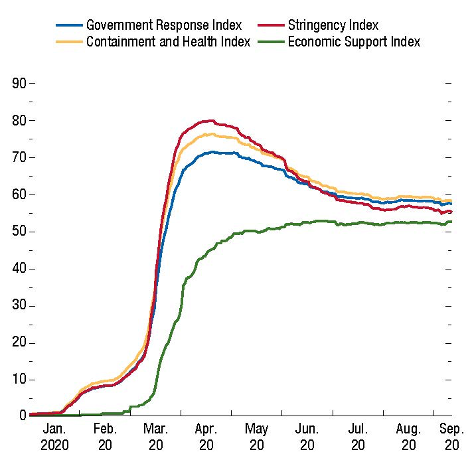

The trend of certain indicators compiled by Oxford University5 is shown in the graph,

as well as their intercorrelation, particularly the economic support initiatives and epidemic containment measures.

The intensity of these measures must be weighed against the risk of an unprecedented recession and the deep wounds inflicted by the epidemic, particularly evident in relation to the labour market.

According to the International Labour Organisation, the global working time lost in the second quarter of 2020 (compared to the fourth quarter of 2019) was equivalent to the loss of 400 million full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs, in addition to the loss of 155 million FTE jobs already recorded in the first quarter of the year.

As mentioned, the main services sectors have contracted sharply, while the manufacturing sector as a whole held up, partially cushioning the impact on labour.

Massive support schemes were rolled out to dampen the impacts of the health emergency, relinquishing conventional tools and austerity measures, with governments having greater discretion to manage spending, even in places – such as Europe – which had previously pushed back strongly against expansionary measures not covered by structural funds.

The International Monetary Fund’s Fiscal Monitor report estimates that these policies account for 9 percent of global GDP, plus another 11 percent for various forms of liquidity support, including equity injections, asset purchases, loans and credit guarantees for businesses and households.

As mentioned in the beginning of this report (see I PREFER TO REMEMBER THE FUTURE), this radical change in economic policies6) has led to innovation and a new conventional wisdom.

The most large-scale example is the €750 billion European recovery fund, over half of which in the form of grants and which will, moreover, be funded by bonds that will be issued and placed centrally.

The broad array of measures implemented globally include cash transfers and grants to businesses and households, wage subsidies and support to protect employment, deferrals of social security payments and taxes, and an easing of the capital ratios for the banking system, particularly as relates to non-performing loans.

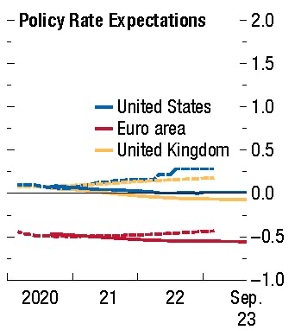

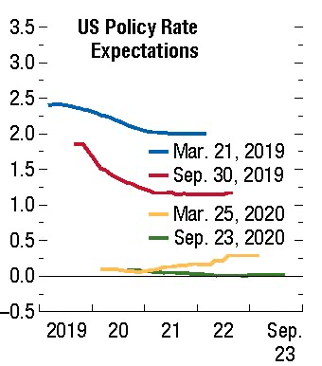

The measures deployed by the central banks of the advanced economies included massive asset purchases, credit lines for bank refinancing, and even a radical overhaul of monetary policy to boost medium to long-term inflation trends.

Indeed, the Federal Reserve has set a target of 2% inflation, while the central banks of emerging countries have largely employed a combination of interest rate cuts, financial support for retail banks and, for the first time, securities purchases.

Monetary policy has therefore generally been key to supporting struggling businesses, households and operators, with the aim of carrying entire economic sectors through to the post-Covid stage and, above all, trying to prevent the amplification of the effects of the epidemic.

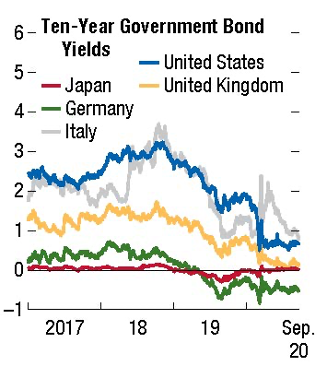

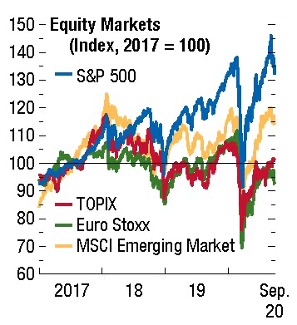

Equity markets7) in the advanced economies have generally recovered the ground lost in the March/April shock, in some cases returning to levels seen at the beginning of 2020. Sovereign bond yields remained largely unchanged, while in some cases such as Italy, they decreased after June, with the European Central Bank approving the massive recovery plan and ramping up its bond purchase programme.

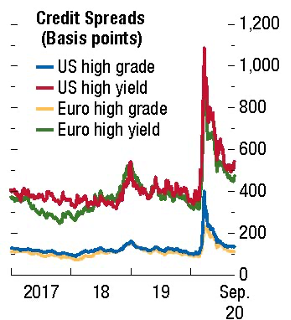

Over the same period, interest rates decreased due to both the lower returns on safe assets and the narrowing of risk premiums.

Credit spreads quickly returned to pre-crisis levels, in some cases benefiting from the radical expansionary overhaul of monetary policies, as in Europe, and the establishment of extensive guarantees.

As regards the currency markets8, the US dollar depreciated by over 4.5% in real terms between April and September, reflecting growing concerns about the trend of the epidemic in the United States.

Over the same period, the Euro appreciated by almost 4%, on the back of expectations of improved health and economic conditions in the European countries. Concerns then arose in November in relation to the progress of the US presidential elections, the outcome of which later boosted market optimism about the administration’s new direction, both in domestic policy, which Biden has clearly oriented towards social reconciliation, and in international relations.

Industrial Production: source Haver Analytics. ↩

Global trade and industrial production: source CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis: Haver Analytics. ↩

Retail sales, source; IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2020. ↩

Consensus Economics, Haver Analytics, October 2020. ↩

Source: Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker. ↩

Policy Rate Expectations, source: Bloomberg Finance LP; Haver Analytics, IMF (WEO, 10.2020 ↩

Policy Rate Expectations, source: Bloomberg Finance LP; Haver Analytics, IMF (WEO, 10.2020 ↩

Source: IMF (WEO, October 2020). ↩

![MAG Annual Report 2020 [EN]](https://finance.mecaer.com/2020en/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2021/02/MAG2020.png)